Limits of Biblical Authority

“Have you not read what David did when he and his companions were hungry? He entered the house of God and ate the bread of the Presence, which was not lawful for him and his companions to eat, but only for the priests.” Matt. 12:3,4

The story is a familiar one from the gospels. Jesus and his disciples satisfy their hunger by going through the fields on the Sabbath to glean grain by hand. The indignant response was immediate. Experts in the law accuse the Lord of violating Scripture. The Jewish Bible forbids such activity on the seventh day, they pointed out.

What did Jesus say? Did he deny their charge? No, instead he declared his authority over the Sabbath. He also reminded his antagonists that even David set aside the letter of Scripture for the sake of a higher priority. Jesus argued for the right to do likewise and glean on the Sabbath.

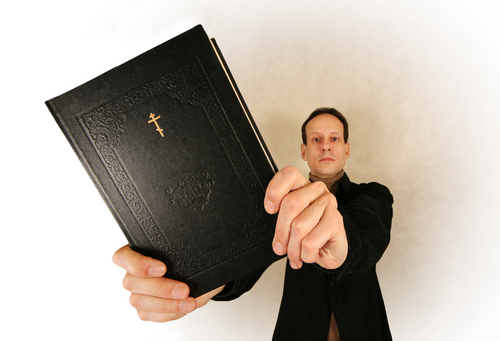

If this text means anything, it asserts that the authority of Scripture is not absolute. Of course, it does wield an exalted authority for the Christian. It is the highest literary expression of the church and Old Covenant Israel. It bears the inspiration of God, a principle that makes the book profitable for “teaching, correcting, rebuking and training in righteousness” (2 Tim. 3:16).

But the Bible was made for humanity, not humanity for the Bible. Jesus and David have set an example of us. Their actions tell us that not all Scriptural texts can be binding for all people at all times in all circumstances.

Some object, understandably, that such an attitude leads to a “picking and choosing” of what to obey and what to believe. The danger exists, of course. But there is danger in all liberating truths. There is a chance, for example, that if we preach the forgiveness of sins, some may say, “Let us do evil, that good may come.” There is a chance that if we proclaim freedom from the law, some may “turn the grace of God into lasciviousness.” The problem is as old as the faith itself.

But if we seek a right heart, we have nothing to fear. People don’t hunt out “loopholes” when they are seeking to love God and neighbor. They simply apply Scripture as best they can in an intelligent and spiritually minded manner. They follow the Bible’s spirit without becoming chained to the letter.

The Bible’s role as a means of grace must be higher than its role as a dictating authority. From generation to generation, the church has used Scripture to encounter the Sacred. It has helped reshape people into the image of Christ from earliest days. How could it have a higher purpose than this?

True, it has helped solve theological disputes and has provided underpinnings for belief systems. But this is secondary — greatly so — to its role as a conveyor of divine goodness. If the two greatest commandments are supreme love for God and neighbor, then the greatest purpose of the Bible must be to foster such graces.

After all, the idea of a book acting as our absolute authority doesn’t get much support in the New Testament itself. Jesus says nothing about the coming of the canon or its role as our supreme guide. He does foretell the advent of the Spirit, whom he said would teach his followers all things (John 14:26). Elsewhere we read that we have an anointing that makes it unnecessary that any man teach us (1 John 2:27). Unlike the Old Covenant law, we have a law inscribed on the heart and mind (Heb. 8:10) — not on tables of stone (nor on parchments, for that matter).

And so the inflexible authority of all Scripture is less a Christian idea than many suppose. The original documents of our faith say little about such a thing.

Not that I’m advocating a modus operandi for “doing theology” that is based primarily upon mysticism or intuition. We need the Scripture. Writings so near to the time of Jesus and the apostles carry great weight. But several considerations suggest that their authority is limited, not absolute. Limiting principles must be permitted to supersede “chapter and verse” at times if our faith is to retain a full measure of common sense.

The First Limiting Principle: Stages of Development in Religious Thought

The Bible is a book that outlines a development in religious thought, from comparatively primitive ideas to more advanced. It does not present a series of full-blown, well-developed concepts from the very beginning. We can track a clear growth of ideas — doctrines of God, redemption, afterlife, ethics — from Genesis to Revelation.

The doctrine of God, for example, passes through several stages as we move through the Sacred Volume. In the opening book of the Bible, God appears as a physical being who walks with Adam and Eve in the garden (Gen. 3:8). He must come down from heaven to see if Sodom and Gomorrah are as bad as the reports He has heard (18:20-21). He repents at making the human race (6:6). His ultimate concern extends only to the Israelites, His chosen race (Deut. 7:7).

But when we advance into the Old Testament prophets, the thinking is loftier. God is the one God of all the earth, there is no other (Isa. 45:21). He has a plan for all mankind (Isa. 25:6-8). He does not change His mind (Mal. 3:6). There is no limitation on His knowledge (Prov. 15:3). And by the time we reach the New Testament, God is a spirit (John 4:24), not a being with bodily parts.

The same patterns of development exist in relation to ethics, the appropriateness of war and violence, monogamous marriage, wealth and racial privilege. We witness a movement from less sophisticated ideas, spiritually speaking, to more sophisticated.

Therefore, early versions of such concepts must not serve as our absolute authority today. We cannot allow Joshua or Gideon to be our guides for the treatment of enemies. Nor can Jacob furnish an appropriate model for marriage. We do not look to Moses to inform us about the nature of wealth, and its relationship to righteousness.

Instead, we seek out revelation in its fullest bloom, in the teaching and example of Jesus Christ, and in the continual unfolding of truth within the church.

The Second Limiting Principle: The Trajectory of the Gospel

Individual portions of the Bible, even New Testament passages, must yield when they conflict with the tenor and trajectory of the gospel message. An example: Paul told slaves to obey their masters (Col. 3:22) and for masters to treat slaves fairly (4:1) — but not necessarily to release them. Abolitionism never occurred to Paul, a man living in a culture that unquestionably accepted slavery. But the trajectory set by the teaching of Christ ultimately precludes the institution. If we accept the premise that we should love all humanity and treat others as we would have them treat us, slavery becomes unthinkable — even if a Bible verse somewhere permits it.

The great themes of the gospel, the broad-brush strokes of Christ’s words and example, sometimes overrule individual verses.

The Third Limiting Principle: Pre-scientific Information

The Bible was penned in a pre-scientific era. We know now that the earth is round and does not have “four corners.” The earth moves around the sun, not vice versa. And it is extremely unlikely that God created the earth before the sun and stars, as Genesis records.

The Bible’s main purpose, as stated earlier, is to create a right heart it us. It is not a textbook for botany, zoology, paleontology or astronomy. Those who embrace such an assumption have the Herculean task of harmonizing ancient, pre-scientific data with some very hard evidence. Better to let this doctrine go and spend our fleeting years here in more fruitful pursuits.

It seems obvious that the Bible’s authority does not extend to matters of science. An insistence upon it often keeps thinking men and women out of the church — a loss for them and for the body of Christ.

Other Considerations

There are other times when higher considerations take priority over chapter and verse. In the gospels, Jesus makes it clear that divorce is not an option, except in cases of sexual immorality. This must have caused some problems in the Corinthian church, when Christian converts found themselves abandoned by their pagan spouses. Were they forced to live out their days in celibacy? Paul didn’t think so. He told them that believers were not bound to spouses who had left them (1 Cor. 7:13-15). God has called us to peace, the apostle said (v. 15). Peace is higher than the letter of Scripture, according to the liberal-minded apostle.

Because God has called us to peace, it makes sense that other exceptions exist beyond abandonment. Must a wife stay with a husband who beats her or uses drugs or is a raging alcoholic? Many of us do not believe so. God has called us to peace.

Because God has called us to peace, men need not battle their wives for “headship” in the household. So many read Paul’s words on the submission of women and conclude that their marriages must reflect this order, come hell or high water. The result is endless discord and struggle. In such cases, for the sake of peace, it seems reasonable that a man may lay aside the Pauline ideal. Peace must be a higher consideration than this.

Giftedness is sometimes a higher consideration than the letter. Paul did not permit a woman to teach, or even to speak in the assembly. But God has gifted some women in the area of teaching. Must they stifle their gifts for the sake of conformity to a couple citations in the epistles? It makes little sense that they should.

Love is also a higher consideration. We are forbidden to lie, so says Scripture. But for the sake of love, we dare not answer some questions truthfully. Love prompted Christians to lie to the Nazis about harboring Jews. It prompted midwives in Egypt to lie about the birth of male Hebrew babies (Ex. 1:16-21). Love is the greatest of virtues and must always be preeminent over all things.

Obviously, we ought to exercise great care when applying these limiting considerations. For example, there are some times when peace is not a higher authority than Scripture. We cannot ignore blatant evil or accommodate sub-Christian ethics to “fit in” peaceably. It requires wisdom and sanctified common sense to know when peace, giftedness or love rise above the letter of Scripture. But the inherent pitfalls do not absolve us of our duty to think, to work out the implications of faith even when there is no “proof text” to rest upon.

To those who argue that such a struggle leaves us without a absolute, infallible standard, I concur. But I would add that the perceived need for such a standard is really the all-too-human need for security. God does not always grant us such security in this life.

Sometimes we must be content to look in a “glass, darkly” and trust in a God who leads us even when the path is not as well-marked as we would like.