The Spirit Within, or Where the Wild Things Are

[A pdf version of this commentary to print and read can be found here.]

Spirit of God within me possess my human frame

Spirit of God within me possess my human frameFan the dull embers of my heart, stir up a living flame

Strive till that image Adam lost, new minted and restored

In shining splendor brightly bears the likeness of the Lord.

Spirit of God With Me, Timothy Dudley Smith

When children’s storybook writer and illustrator, Maurice Sendak, died recently, generations of parents and their kids undoubtedly paused for a moment to recall earlier days; and briefly returned, with their imaginations still intact, to the place he so vividly described Where the Wild Things Are.

In the storyline, mischievous Max in his wolf’s costume is sent to bed without supper for rumpus-making, but his imagination remains untamed. He sets sail for the place where fearsome monsters dwell, only to stare them down, win them over and become “the king of all wild things.” [Sendak once remarked the that idea for the wild things was inspired by the Yiddish expression “Vilde chaya”, a reference to boisterous children.]

Eventually Max becomes lonely and homesick. Returning to the world of mothers and fathers, families and households, he finds himself in his bedroom once again, with his supper still warm and waiting for him.

It is one children’s version of the archetypal story of prodigal journey and joyful, grace-filled return. And in the meanwhile, there are those lively moments in time and place that remind us that there can sometimes be more reality expressed in spirited fantasy than the dull perceptions of the real world that would feign to define reality. Things are not always what they appear to be, so it’s best to look within.

“Vilde chaya”, boisterous one, is also what I think of when I think of spirit; as in holy spirit. As Robin Meyer’s remarked in his latest book, The Underground Church: Reclaiming the Subversive Way of Jesus, it’s like the “prodigal child that leaves home and then shows up without warning.”

It’s also like the wind that cannot be harnessed; and the flame that can enlighten, purify, and reduce to dust and ashes the timbers that would sometimes seek to encase it. Beware is the message to what some call “church.” There’s something afoot.

So it is that I’ve thought about this spirit of God, and the place from which it springs. It’s a place where the wild things are. And I’ve also thought about it in terms of those shrines we like to construct in which to enshrine it, define it, and some even claim to dispense it with presumed proprietary rights.

There are those religious traditions within the Christian faith that speak of sacraments as the conferring of “gifts” of the holy spirit; like baptisms, or eucharistia (thanksgiving), or ordination. So wondrous are they that they’re meant to leave such an impression as to be indelible. It’s strange therefore when those who claim the right to dispense such gifts occasionally even ask for them back.

Last year, when an earthquake demolished the beautiful cathedral in Christ Church, New Zealand, it should have been clear to anyone God doesn’t play favorites.

But when the pinnacles of the National Cathedral in Washington, DC, were damaged by another quake that followed on the other side of the world, I wonder if I was the only one on the face of the earth who wondered if that wild spirit that “blows where it wills” whenever it wants wasn’t trying to tell us something.

Then when I recently read the attempts to raise funds to rebuild the damaged temple in DC was lagging far behind, I also wondered if folks nowadays were trying to tell the temple-keepers something.

In the mid-Sixties, my late father, who was at the time the Episcopal bishop of Western Michigan, built a magnificent cathedral in Kalamazoo, that many considered an architectural masterpiece. With waning financial support for the message of a mainline church that’d lost its voice, the building and surrounding acreage was sold off a mere half century later for a pittance to Valley Family Church, a non-denom mega-church that uses the original building as a wedding chapel.

Inside, the cathedra, the presiding bishop’s chair that resembled a stone throne is long gone. The whereabouts of the spirit that once inhabited those four walls – and presumably still does – is anyone’s guess

And finally, when Robert Schuller’s Crystal Cathedral was sold off earlier this year to the local Roman Catholic Archdiocese in Anaheim, I couldn’t help but call to mind the cautionary adage for the new tenants, about “those who live in glass houses …”

So it seems that religion of any stripe or color would claim to invoke and accommodate the spirit of what we might define as divine. But for anyone who would describe themselves as spiritual (if not merely religious) what kind of spirit might they mean?

People periodically speak about the “indomitable human spirit,” that perseveres and presses on against all odds. Others talk about that divine, “holy” spirit that comes out of nowhere from somewhere outside us, and then inspires us from within. Sometimes it is said it nearly overtakes us, and changes everything; or at least changes the way we perceive and relate to everything from that point on. Some call that conversion.

Other times we just call it “divine inspiration.” It is that elusive and intangible spirit that is at the same time within us — but not a part of our own conjuring — that constitutes both that tenuous thread and tether of a relationship with whatever we might call the holy divine.

It is that elusive and intangible spirit that is within us … that constitutes both that tenuous thread and tether of a relationship with whatever we might call the holy divine.

Here’s the thing: that “holy” spirit that dwells within is as elusive as it is pervasive. Lord know, we’ve tried in vain to harness its life-giving energy, traditionally symbolized (in scripture and elsewhere) as wind, or breath, or fire. [Okay, doves too, but I’ve often thought there’s little difference between a dove and a pigeon. And personally, I just can’t go there.]

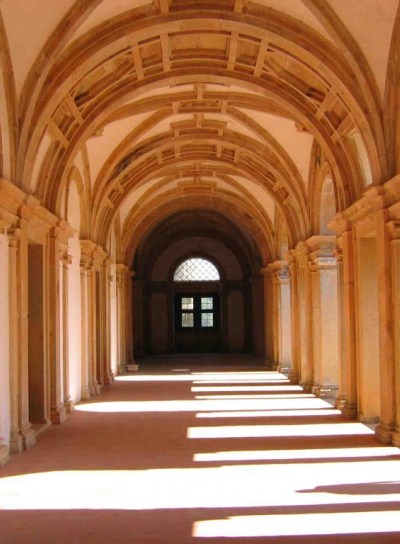

Now clearly, the most recognizable place we’ve tried to corral this life-giving spirit is called the institutional Church, with a capital ‘C.’ In that process, the temple within has become externalized to become as tangible as brick and mortar, consisting of steeples and spires.

Then, with flying buttresses supporting it all from the outside, ecclesiastical authority holds audience inside; often enthroned on their cathedra in tableaus not unlike that of revered royalty, bedecked in garb that might make a monarch blush with envy.

With tongues of fire resting on their heads, the miter becomes mightier than the crown; as earthly authority is claimed by a presumed right of apostolic succession. With shepherd’s crook in hand, they would defend the flock; assuring salvation by formulating doctrines of what to believe about the Holy Spirit, and just about everything else.

Everything else could be about women’s reproductive rights, or religious freedom, or immigration reform. It could stem from religious conviction and prophetic proclamation; or sometimes the fear of their own temporal authority becoming further eroded by their own irrelevance and pastoral amnesia for those whose real needs and rights are presumed to be the whole reason for such a grand enterprise in the first place.

But that divine spark that dwells in each of us cannot be domesticated — let alone indoctrinated — within the confines of any religious tradition, if it is not first inspired with that first breath of what all great religious traditions identify in one form or another as simply spirit.

This is the time of year when many Christian communities observe the “gifts of the spirit,” as they were once bestowed like tongues of fire on a few of the first People of the Way (of Jesus). We recount those familiar lines from that bizarre scene in the upper room where the timid and speechless huddled in fear.

The wind blows down the locked doors and fire nearly consumes them: “Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared among them … And rested on them. All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit.” (Acts 2.3-4)

Then, after such an ecstatic experience, the Church takes a couple centuries to confiscate the story in a power grab, and come up with that confounding invention known as the Trinity, and subsequent Trinitarian creeds: “We believe … we believe … we believe …etc., Amen.”

In reality nowadays, this familiar creedal form by which many of us have known what “church” is presumably all about in an Age of Belief, has gone the way of all hierarchical human institutions. Its dwindling days are obvious to many.

Where once there was something passionate about the Kiss of Peace, it has been replaced with sleepy sanctuaries of tranquility; where the tempestuous wind has only been stilled to calm our fears, and the fire snuffed out like the last altar candle to indicate the worship hour is finally over.

But whether you want to call it renewal, restoration or even a kind of spiritual revolution, there is also the emergence of what some call the “subversive way of Jesus” that — like its original inception — has had little to do with so-called organized religion; and instead returns once again from where the wild things are to unexpectedly rush in a breath of fresh air with the kind of message the Galilean spirit/sage might, in fact, still recognize.

Some illustrative examples:

The canonical gospels are littered with those stories of conflict and confrontation between Jesus and the temple authorities of his own religious tradition; who are typically depicted as entrenched in theological debates about what to believe, or not believe, as justification for their power and authority. They grumble endlessly about the infractions with their rules and regulations.

“Beware of the scribes,” the Jesus character in Luke’s gospel is attributed as saying, “who like to walk around in long robes, and love to be greeted with respect in the market-places, and to have the best seats in the synagogues and places of honor at banquets. They devour widows’ houses and for the sake of appearance say long prayers.” (Luke 20:46)Or from Mark’s gospel,

“‘You have a fine way of rejecting the commandment of God in order to keep your tradition! … Then he called the crowd again and said to them, ‘Listen to me, all of you, and understand: there is nothing outside a person that by going in can defile, but the things that come out are what defile.’” (Mark 7:14-15)The Jesus of Mark’s gospel repeatedly challenges the “externals,” and – in doing so – challenges one of the most telling truths that are continually snuffed out; namely that perception (outward appearance and behavior) does not, in fact, define reality.

Or, at any rate, the kind of ultimate reality Jesus is talking about.

The Jesus character in Mathew’s gospel reflects the struggle already underway in the early church formation when in the same chapter (16), Peter is first called the Rock (petros) “upon which I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.’”

But only a few verses later when the passion of Jesus’ suffering, death and resurrection is retrospectively predicted, Rocky is called Satan instead; with his human agenda of earthly concerns. Proprietary claims (i.e., just who’s got the key’s to unlock Paradise’s door?) are evidently already underway towards the end of the first century CE when the gospel writer constructs this tale.

’And by the time we get to John’s late gospel, we have a surreal dispensation of spirit to the early church where the ethereal and physical worlds are conjectured with a risen Jesus with corporeal wounds clearly visible appearing through locked doors to fearful followers who’d never known an earthly Jesus.

‘Peace be with you.’ After he said this, he showed them his hands and his side. Then the disciples rejoiced when they saw the Lord. Jesus said to them again, ‘Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, so I send you.’ When he had said this, he breathed on them and said to them, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.The Galilean sage who once taught only the sinless should dare cast the first stone has faded like a distant memory. Forgiveness becomes a transaction to be dispensed by authoritative means, and you’d better believe it, or else. Just to make sure, so as to not leave any doubts, Thomas gives it a try.

But Thomas (who was called the Twin), one of the twelve, was not with them when Jesus came. So the other disciples told him, ‘We have seen the Lord.’ But he said to them, ‘Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe.’ A week later his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them. Although the doors were shut, Jesus came and stood among them and said, ‘Peace be with you.’ Then he said to Thomas, ‘Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe.’ Thomas answered him, ‘My Lord and my God!’ Jesus said to him, ‘Have you believed because you have seen me?’ (John 20)“Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe,” says this fictional Jesus of an early, institutionalized church in the making. After all, seeing is believing. Who needs the spirit within? After all, who needs spirit when you’ve got physical evidence?

Conversion becomes a matter of creedal conscription. The spirit that once was “king of all the wild things” that God has so grace-fully done in our lives no longer requires our conviction, only adherence to a set of beliefs.

But if I believe anything I believe this. The spirit of God within us cannot be tamed.

And, if such a grand “consideration” as Christianity has a new day dawning I have a growing suspicion it will hearken back to the life spirit in a kind of “church” the only way those first followers of the Galilean sage could have done it; when there was only a “house” church in which to gather, and the only temple to attend was the temple within each of us that was to be attended to.

It may, however, require more of us than muttering a few acceding words about what we merely believe.

If you think it’s tough swallowing a doctrinal creed hook, line and sinker, try to imagine playing with a little fire, as did the “People of the Way” (of Jesus). Consider the possible consequences of actually living what we’re saying or singing:

Tune our hearts to sing your praise,let our voices gently raise

Sweet desire, your holy fire,

stir in us through all our days.

Words & music by S. Steward & J. Bennison, 1988

© 2012 by John William Bennison, Rel.D. All rights reserved.

This article should only be used or reproduced with proper credit.