Why God Imagery Matters

In the opening sentence of her book A History of God, Karen Armstrong wrote: In the beginning, human beings created a God who was the First Cause of all things and Ruler of heaven and earth.[1] I would ask students in my Science and Theology class what Armstrong meant by this statement. Ultimately, they came to understand that she was referring to God Imagery, what we imagine God to be. Armstrong continues for 399 pages to chronicle how many different religious traditions interpreted what God was to them. At the end of the day, God defies description because no one has ever seen God.

Despite this, humans continue to conjure up images of God that provide them the comfort of relating to something tangible. However, Armstrong was not alone in wanting to call attention to how God imagery impacts humans. Marcus Borg wrote: Tell me your image of God, and I will tell you your theology.[2] Lutheran theologian, Dorothy Solle wrote: Tell me how you think and act politically and I will tell you in which God you believe.[3] Both of these quotes reveal the pervasive nature of God imagery for many who have not examined the difference between an imagined image of God as metaphor versus a more nuanced understanding of God.

Among the more pervasive stereotypes of God is the use of the male pronoun” He” that anthropomorphizes God in our image. Over the years, this paternalistic depiction of God has done more harm than good. Nor is it useful to portray God as a female deity. Both pronouns are metaphors for God. Also consider the role that art has played over the centuries that contribute to reinforcing iconic images of God. For example, Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam in the Sistine Chapel depicts how God is literally viewed by many.

The legitimation of Christianity by the Emperor Constantine in the Edict of Milan 313 CE was the beginning of the transition of the fledgling church into a model of the Empire. The Council of Nicaea cemented an imagery of a supernatural theistic God[4] who was “the maker of heaven and earth” in the Nicene Creed as a complete articulation of the Christian myth circa 325 CE. Thus began the infantilization of Christianity that viewed humans as supplicants to an “Almighty” God, begging for intersession and forgiveness. With God in control, what role do we humans have in the Creation? For the above reasons, my personal preference is to refer to myself as a non-theist.

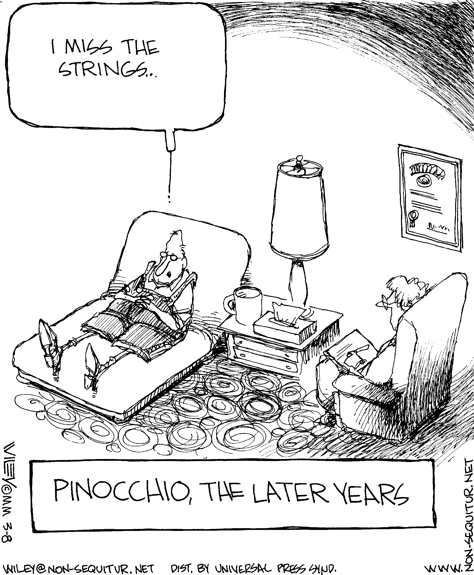

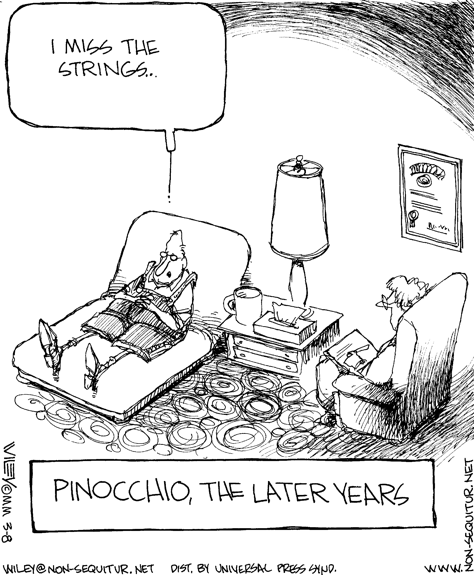

Wiley Miller’s cartoon of Pinocchio on the psychiatrist’s couch speaks volumes to how we humans yearn for someone else to be in control rather than assume personal responsibility. For many that “someone” is the God in absolute control, the one who manipulates by pulling the strings or intervenes as a “designer” God in biological evolution. This is the same God that many love, but also hate when God does not answer prayers to their satisfaction.

How do we get out from under this oppressive theology to rediscover our role as Christians who have a responsibility to live into what it means to be followers of Jesus? First, we need to stop viewing ourselves as supplicants or victims of a MAN made, Top-Down system and begin to assume our full responsibility as participants in the creation. In a previous publication in Progressive Christianity[5], I advocated from a scientific viewpoint that God was not the literal Creator of the universe nor the responsible designer of life that evolved in a complex way that we call evolution. It is difficult for us to acknowledge that we humans were not intended, however, it is crucial to evaluate this possibility for us to move forward. This begs the question “What role God?” A suggestion was offered in that article that God simply loved the Creation into existence and let it be.

This diminutive role of God is unlikely to be accepted by many Christians who have already conceded that their God is literally in absolute control. However, we must realize that there are major consequences to this depiction of God. If God is in absolute control, then everything that happens has been ordained by God whether we are satisfied with the outcome or not. This is where believers often have difficulty with God because they believe that God was responsible for tragic consequences that occur. In addition, they also believe that the good things that happen are also a result of God’s intervention. Yet, how often do our prayers go unanswered, at least according to our expectations. Theologians have a term for this, theodicy (Can God be justified in light of evil and suffering?). Unfortunately, bad things happen to all of us at some time in our lives. And when they do, it is commonplace to want to blame someone or something. God becomes a readily available foil for our frustration, often contributing to a loss of faith/belief. We humans have a difficult time dealing with uncertainty and ambiguity.

Despite our classic refusal to accept personal responsibility for our lives, the above depiction of a humble, “hands off” deity offers a liberation out from under an oppressive brand of Christianity that many have simply acquiesced to embracing without question. No matter who we are, or what we have done, God loves us for no reason. We do not have to earn grace from God, it is there for the offering. Theologian Sallie McFague writes: …the most important characteristic of God’s life is love. Here we have the one word that we use to talk about God that is not a metaphor; that is something drawn from our world and used—stretched—to function somehow for God.[6] If we gratefully accept this offer of grace, how can we express our gratitude?

This God concept imparts a “God likeness” to each of us, providing we are open to receiving it. This begs the question; how then do we pray? If we have assumed the incarnational role of being God-like, praying to God becomes problematic, because when we pray to God, we are asking God to intervene to answer our prayer “for” someone or something. Are we being selfish to request an answer to our personal prayers?

Alternatively, I suggest that we consider praying “with” instead of “for” when offering prayers, because I personally do not expect God to intervene based on my understanding of cosmology and evolution. Praying with someone is extending our own God likeness to the other, no matter where they may exist on planet earth. This is not unlike quantum teleportation, or quantum entanglement, “strange (spooky) action at a distance”, that Einstein struggled with. Entanglement reveals that particles that decay from a state of superimposition share a quantum entanglement. If one particle changes spin, the other instantaneously changes to an opposite spin no matter how far apart they are in the universe. Einstein’s angst was if entanglement happened, it had to occur at speeds faster than the speed of light. [The Nobel prize for physics was awarded in 2022 to three scientists who contributed to proving that this quantum phenomenon exists.]

Ultimately, this kind of thinking both scientifically and theologically contributes to a liberation out from under the concept of God being in absolute control. Instead, it places the responsibility for God’s actions squarely in our own hands as agents of God, using our gifts and talents for the betterment of humanity and the creation. Jesus of Nazareth was the epitome of how to use one’s gifts in the service of others. Failure to acknowledge our God likeness is an abnegation of our Christian responsibility.

I once was scheduled to give a talk on Science and Theology for which there was some advance publicity in our local newspaper. Out of the blue, I received an email from someone who wrote, “You sound like you need God”. I responded to him, “I do not NEED God, I live with God”. I never heard from him again. I am reminded of apophatic or negative theological thinking, where one can only say what God is not. This is compatible with how I understand the mystics lived with God. Defining God for them was not important, however, an intimate connection or union with God was ever present.

In conclusion, how we view God matters because many have modeled their behavior after how they have imagined what God is to them. Much of that imagery is a result of our early Christian education that shaped our imagination that many have not outgrown. Few have begun the process of “deconstruction” of their childhood instruction. In addition, most practicing Christians are not aware that when they worship, they are participating in the Christian myth or story that is not literally true. Further, if we literalize the myth, we eliminate the beautiful role of the imagination as invitation into the story and become “fundamentalists”. Maybe it is time to remythologize. Perhaps the best indication of the beginnings of the acceptance of a new mythology is the relatively recent recognition of the common purposes and understandings of the old enemies, religion and science, spirit and reason. At the progressive fringes of even mainline religious traditions we now find people who no longer speak of our patriarchal right as a species to conquer nature and rule the world but rather of the importance of human consciousness as a functional aspect of earth and creation itself. These people are concerned with better understanding the myth of God in light of our deeper understanding from physics and biology of the interrelatedness of all aspects of creation.[7] One of the problems of Christianity today is that it has not done a good job of inviting followers into the questions. Until that evolution begins to happen, we will continue to succumb to an infantilized form of Christianity.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

————————————————-

[1] Karen Armstrong, A History of God, Ballantine, New York, 1993, p.3.

[2] Marcus Borg, The God We Never Knew, HarperCollins, San Francisco, 1997, p.57.

[3] Dorothy Solle, Thinking About God, Trinity Press, Philadelphia, 1991, p.8.

[4] Richard Swinburn, The Coherence of Theism, Oxford U. Press, 1977, p. 1. Theism: A view of God that is “something like a person without a body, who is eternal, free, able to do anything, knows everything, is perfectly good, is the proper object of human worship and obedience, the creator and sustainer of the universe.”

[5] Thomas Lindell, “A New Year, A New Beginning”, Progressive Christianity, February 6, 2021.

[6] Sallie McFague: Collected Readings, David B. Lott, Ed., Falling in Love with God and the World, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 2013, p. 260.

[7] David Leeming, Myth: A Biography of Belief, Oxford U. Press, New York 2002, p. 24.