My Robot, My Self

on AI, religion, and

A few weeks ago, when I found out that my books are among the many thousands that have been fed into a large language model for the purpose of teaching artificial intelligence, I didn’t know how that was supposed to make me feel; Should I be honored they made the cut, or horrified that my intellectual property is being made into some sort of soylent green for robots.

Honestly, I am still unsure of the whole thing.

But this week I saw the film, The Creator, a futuristic thriller in which humans developed AI to help in menial tasks, only to have the technology soon simulate human beings – the simulants eventually manifesting the best of humanity (compassion, faith, altruism) more consistently than actual human beings. Many humans have developed loving bonds with the simulants, bonds that are rebuked with the phrase “They’re not people. It’s just programming”. But the programming is only ever done by people, and so the question of the film (much like in Blade Runner and Battlestar Galactica, and Ex Machina among many others) becomes, what does it mean to be human.

As we look down the barrel of the AI gun, with our heads full of cautionary science fiction tales, not knowing if we are facing Wall-E or HAL, we’d do well to access the kind of thinking that for millennia has asked the biggest questions. I am referring of course, to religious thought.

When asking what it means to be human, let’s remember that humans have always been religious – we are meaning making animals who have fashioned our spiritual symbol systems in endless variety for the purpose of speaking about the Big Ideas. (Who are we? Where did we come from? Why are we here? What happens when we die? What is a good life?) There’s some pretty good stuff there.

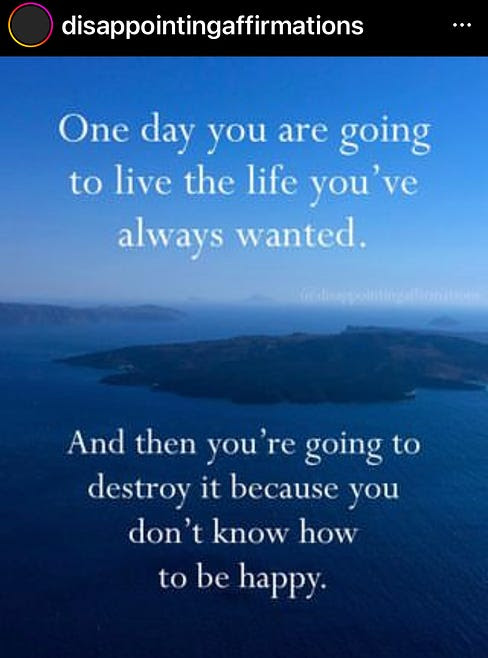

So in the question of what it means to be human, we might aim our sight just slightly above the horizon of high self-esteem porn doled out by Instagram Influencers. (You can have it all! Just manifest your dreams! You deserve to be anything you want to be in the world!) As (understandably) unfashionable as religion is at the moment, perhaps we could just break away from cat videos and make-up tutorials on Youtube for as long as it takes to consider some dusty old ideas that could be helpful right now.

Like … Sin (yuck, I know)

I understand why people are turned off by the word sin – a word weaponized against so many of us. A word used by the priggish to label the Hester Prynnes of the world. A word for those who have fallen for siren’s songs, and taken what is not yours and felt pleasures that good people know better than to indulge – a word for you who have eaten the Turkish delight that the white witch offered.

But Simeon Zahl gave a lecture years ago at the Mockingbird conference in which he claims that though many recoil from the word “sin”, the condition still exists. Not as a list of naughty indulgences one must avoid to be seen as “good” but as a “condition under which human lives exist. Sin is a way of describing the fact that there is a fundamental flaw in the human system and is an explanation for why that system keeps throwing up errors… plans go wrong, communications fail, good intentions decay and corrupt—and [as a way of] describing the fact that, in so many things that happen, there is this slight tilt towards the perverse and the cruel.”

Zahl goes on to claim that what theologians have always called “sin” hasn’t gone anywhere, it is hiding in plain sight as what social psychologists call “cognitive bias”: the ways we deviate from rationality that causes us to perceive reality based on our subjective beliefs and opinions rather than any kind of objective truth while convincing ourselves it is REALITY. Humans ignore data that doesn’t suit our self-interest.

Related Post:

Our drug of choice right now is knowing who we’re better than.

Here’s a small example: The Fundamental Attribution Error is a form of cognitive bias in which we tend to attribute the bad things that happen to other people as being a result of their character and the bad things that happen to us as being a result of forces beyond our control.

If my colleague gets fired it’s because everyone knows she is lazy, but if I get fired it’s because the boss is sexist. And if I get a promotion at work it’s because I am a hard worker but if he gets a promotion it’s because he’s always kissing the boss’s ass.

(If you’d like a list of verified cognitive biases, go here.)

Sin and AI

Here’s where I am going with this: Judea Pearl.

Pearl, now 87, is recognized as the godfather of AI, and a few years ago I read an interview with him in The Atlantic and remember finding the last part chilling:

What is evil?

Pearl: It’s the belief that your greed or grievance supersedes all standard norms of society. For example, a person has something akin to a software module that says, “You are hungry, therefore you have permission to act to satisfy your greed or grievance.” But you have other software modules that instruct you to follow the standard laws of society. One of them is called compassion. When you elevate your grievance above those universal norms of society, that’s evil.

So how will we know when AI is capable of committing evil?

Pearl: When it is obvious to us that there are software components that the robot ignores, consistently ignores. When it appears that the robot follows the advice of some software components and not others, when the robot ignores the advice of other components that are maintaining norms of behavior that have been programmed into them or are expected to be there on the basis of past learning. And the robot stops following them.

In other words, when it demonstrates cognitive bias.

I get that talking about this shadow side we all share is not terribly inspirational – it does not fill us with a warm feeling of optimism. And there is a lot out there that caludes in keeping us from the truth – an absolute cadre of power of positive thinking, Purpose Driven drivel brokers cashing in on our reluctance to admit we as humans have an inescapable propensity to fuck things up.

What I am saying is that if we are not looking at the whole reality of being human, the good the bad and the embarrassing, then we simply will not have the wisdom to know how to make use of, them in, or regulate AI.

At this moment in history, we have an opportunity to be honest:

Have we created WALL-E or HAL?

Likely both.

Why? Because we are both.

As Martin Luther said, we are all simultaneously sinner and saint – 100% of both, all the time. We are both cruel and tender, pathetic and noble, honest and filled with deceit.

And it’s ok. Without this complexity there would be no art, no forgiveness, and nothing would ever be funny.

But if, as Zahl says, there is a flaw in our system – if part of what it means to be human is that we are glorious and also tend to muck things up, then any human endeavor no matter how inspiring, is susceptible to this condition, and that includes every single word and point of data being swallowed up by large language models, which apparently now includes my own books.

I just am suggesting that as we ask the question, “what is a human being” that we allow the generations of those who came before us (even those much more religious than ourselves) to help us reach for a fuller more honest answer than we may get from a meme on Instagram.

Unless it’s this account. Which I love: